A common question we get is ‘Why…this? The village, the falling down house, difficult working environment, all the risks, the money…’, cue awkward silence.

Our answer hasn’t changed – my heart races every time I set foot in the house. When I look at, touch and smell her walls; the history, architectural finery and flagstones worn smooth by the footsteps of time. Oh if these walls could talk, what things they have seen!

They’ve stood firm whilst the Qing dynasty, the Taiping Rebellion, The Boxer uprising, May 4th movement, the Nationalists and the revolutionaries have all flashed past in a whirlwind, and since faded to nothingness. Some have made their mark on the house. All will have made a mark on the people who’ve lived here. My passion, my wish – is to peel back these layers and bring them to the surface for my own interest, but also to share with an outside world which has been too long locked out of these stories.

If you’ve been to China: Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, maybe even Xi’An and Chengdu you might have wondered where these 5000 years of history is that we all hear so much about. The answer lies away from the rapacious development in the cities, lost up in the hills in the small villages where the diggers have not razed the land for concrete towers. Wuyuan is a shining example of this – always renowned for culture and learning, isolated from modernity by its location.

This post is an introduction to how we started to understand our house. Odds are slim you’ll make it to the end of this piece, but would be far slimmer were I to share everything we’ve learned to date.

I am no Historian by trade; perhaps a passionate layman at best. With this in mind, we went searching for people who could help.

First, our master carpenter YuYouHong (Yuzong) -a national level ‘Champion Of Chinese Intangible Culture’. In this instance, the wood carvings of Wuyuan houses. He is always kind with his time, and has a wealth of knowledge unmatched likely anywhere in the world on this subject. His understanding of the stories painted in wood are unparalleled.

I am also grateful to Nancy Berliner from the Boston Museum Of Fine Arts who has a wealth of experience here with YinYuTang (a fascinating story in its own right, click here to read more) for sharing her time and advice with me. She urged firstly patience – her project had taken 6 years (!) to bear clear stories and to lean on the best resource available – the memories of the old folk in the village.

Thirdly, the Wuyuan through-and-through BiLaoYe – a local historian whom we had met previously and expressed interest in our project. He has spent time with us reviewing the house, its building style, layout and interviewing the villagers. We began the usual approach process for getting someone to do work with us, in this case three restaurant dinners. When we first sat down to meet him, he was squirrelling his way through some sunflower seeds and invited us to sit down curtly, as a 70+ year old academic might. “I’ve ordered food’, he announced. ‘Not sure about the meat though… lamb or dog?’

The inhabitants and villagers, are of course the real heroes here. This is the story, not mine. Teasing it out of them is somewhat of an art though. 20th Century history is not something many in modern China are keen to revisit, let alone their personal role in it.

The children of the revolution

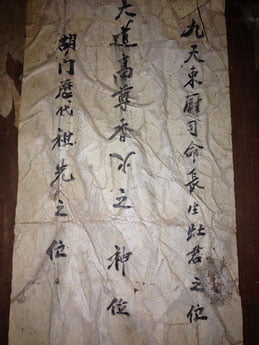

Its impossible to discuss the house without mentioning the revolution. Its prudent for one dealing with the CCP on a day-to-day basis to not dwell on the causes, rights and wrongs of Mao’s ‘Great Proletarian Revolution’… Needless to say, you should have a read for yourself. The attack on the four ‘olds’ (customs, culture, habits & ideas) put the fabulous Wuyuan villages squarely in the firing line. Temples & ancestral halls were ripped apart and used for firewood, stone ground into ballast for new factory foundations. Ancestors, who previously represented a local type of god, worshipped in the centre of each house were cast aside in favour of progress. Family trees, which had been kept for hundreds of years were burned. In the main hall of many old houses reverence turned towards Mao ZeDong who’s smiling face sits where ancestor shrines used to.

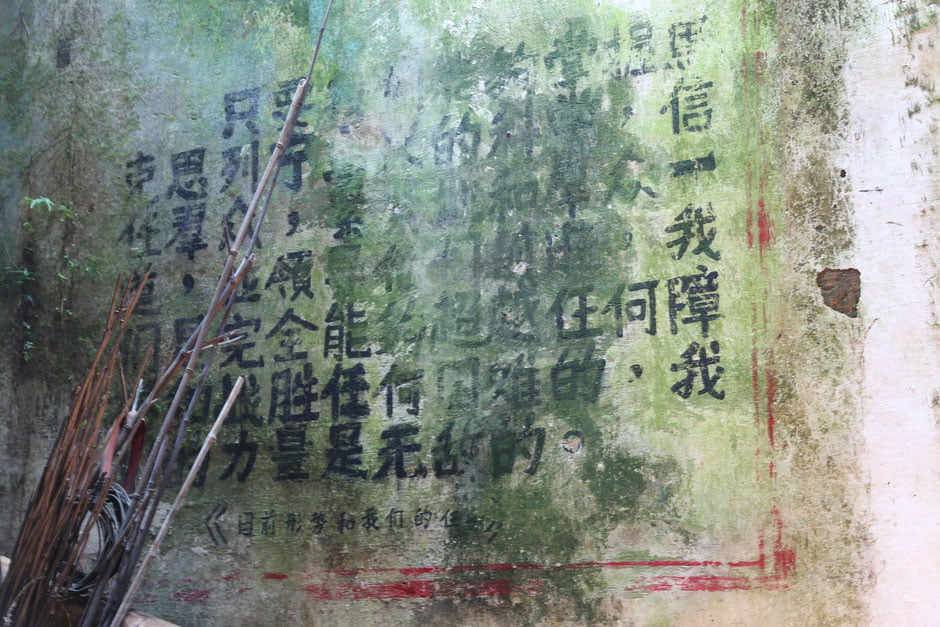

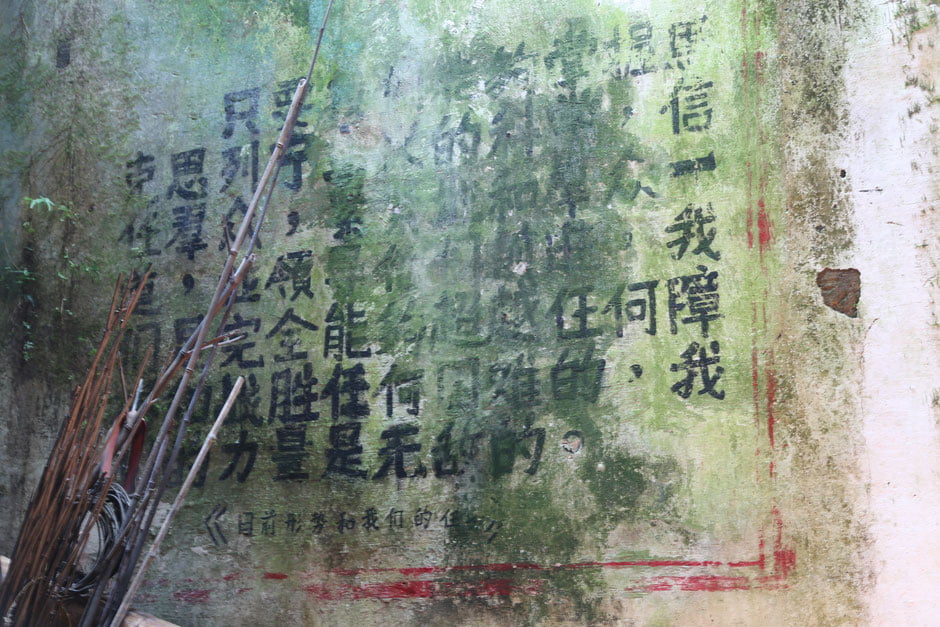

In our house, the heads of figurines carved onto doors were cut off. Red guards had daubed one of the Great Helmsman’s famously catchy quotations on the wall:

So long as we can grasp the science of Marxism-Leninism, gain the trust of the masses, and keep the masses tightly bound together and lead them forward, we are fully able to surmount any obstacle and overcome any difficulties, our strength is invincible.

During this time, anyone who was deemed a ‘landowner’ – someone with wealth, large houses, and land would lose their house and it be subdivided among the masses whom they had been oppressing. In our case, the house was distributed among 4 families, and at one time housed 53 people. Much was said and done in this time, and China bears open wounds still which outsiders are wise not to poke and prod. The villagers are certainly not keen to discuss who’s family lived where and who’s didn’t historically. The discarding of history, records and family trees (one the ‘olds’) means little is known about history stretching back further.

As if this wasn’t complicated enough…

The Lost Boys

Our house was lived in by various families – the ever green 90+ years old Mrs Teng, living by herself with no help. Jin Laoshi, the venerable teacher who values knowledge, culture and learning. Another Mr Jin, fond of long lunches, making introductions, being the centre of social circles. We asked all of them about the history of the house. They shared tidbits, but generally just the nervous grin of awkward embarrassment, when they are not prepared to talk. Our next answer came from humbler origins: Mr Luo – a quiet, hardworking man who focusses on his fields and his family. He does both with aplomb. Over 60 years old, he is fit as a button, and has legs like an Ox. When pressed on the history his pupils dilated and he sat back in his chair, sighing knowingly.

‘It was owned by an old lady once’ he started. ‘My grandfather spoke of her.’ This spinster (called ‘Jin’, of course…) was from a wealthy family, but never married. She adopted boys from the village who lost the parents in the carnage of the early 20th Century, and they lived in the house with her. Some of these boys stayed in the house, and became the families that lived there and in the village up until the revolution. I love the idea our house has been a safe haven for the lost and downtrodden. It also further explains the reticence of the families to talk lineage with us. Orphan status is taboo in traditional China. It also represents yet another break in the continuous story of the house which we will struggle to overcome, and peer into the history that lies beyond like a wall.

Many houses, brought together

Finally, the building itself is a jumble of time periods. Each area has a distinct architectural style, reflecting the time when it was built. Our central skywell is the oldest part of the house stretching back 300 years and is built in thick, heavy square set lines. The entrance hall is newer and has flowing ornate archways, fine wood crafting and a touch of Mao. The pig pens are only functional – and in our case completely caved in. I have been insistent on this palimpsest of time periods since we first saw the house. Windows are different sizes, rooves different heights, door carvings show different imagery. There are clearly some different styles going on here.

This, however, is not in the accepted history of the house, as told by the families. If it was, the revolution, the orphans and the sands of time meant all knowledge of this was lost. I have pushed, pleaded, pointed and argued at length with the locals on this point all to no avail. It is draining to argue your case, in a foreign country, in Chinese for 6 months. Enter, stage left, Bi Laoye. The first time he came to the house, he immediately said it was a very old house, with new formal halls added on as history passes. I was doing backflips and a little dance in my head whilst he was telling the assembled villagers, but giving nothing away on the outside.

This all leaves us in a tricky place. We have a house which is really a few houses squished together, with people who have no idea how their families came to live in the house and wouldn’t tell us even if they did. If the story of the house is an onion and we are indeed peeling back the proverbial layers; then ours is one of those funny onions that has a few more small misshapen onions growing inside, and maybe a bug crawled in and ate half of it, and then another onion shoot grew in the space it left. A strange, dirty, meta-onion.