Everything you thought you knew about China is wrong.

If you live in China long enough, this feeling actually seems to increase, not decrease. Such is the nature of the beast.

Our hotel is located in a small village in Jiangxi province – not a place known for international practices and standards. Having worked in Shanghai for 3.5 years, I had a taste of how things work in China: the relentless energy and long hours of my Chinese colleagues, the deafening silence when people are pushed for an opinion, the vast sums of money and people involved in every project. Overall, my biggest lesson was absorbing the ever present mantra ‘there is no one China, but many Chinas, each over-lapping and interwoven with one another’. These themes should be familiar to anyone who has spent time in the middle Kingdom. Interestingly enough, nearly all of these assumptions appear wrong in my village experience.

If you work in China, you may not think that the business culture of villages, fields and hill farms concern you and your proverbial marketing agency in Shanghai. Just remember, however, that most people in China come from the countryside within the past generation or two; that cultural continuity and family ties remain. Western business practices are a relatively new way of doing things, and bubbling beneath the surface will be an awareness of how things were done traditionally.

I’ve tried to outline some key musings I have learnt from the past year – in buying a house, land, tendering for builders, dealing with the government and ultimately – maintaining and growing relationships.

Lesson 1: Bring A Strong Baijiu game

If you are planning on getting anything done, know how to drink and hold your Baijiu. Baijiu is a grain based spirit, normally clocking in at around 55% Alcohol content. It has a history spanning thousands of years, with many locals believing it has health benefits and will not give you a hangover like ‘those foreign drinks’. It is excellent at helping to get your lawnmower started on a cold morning and will remain on your breath (particularly burps) for seemingly weeks afterwards. As LSD has developed a reputation for flashbacks, with bits of acid popping up in your brain and sending you back to a trippy place years later whilst driving a car – A Baijiu burp is similarly lethal, and days after will pull you straight back to the awful tastes, headache and existential dread of a day-after hangover long after you actually embibed the stuff. Approach with caution, and possibly a crash helmet.

Any reputation the Chinese may have for obfuscating, and dancing around the heart of a subject quickly vanishes after Baijiu. ‘You should give him 1000 RMB and then this problem will be solved.’ As a social lubricant, it is particularly powerful.

One should never simply drink one’s cup, but toast a person each and every time you drink. This may be with one person, a few people or all people at the table, awash with praise, reminisce and a spot of brown-nosing. This leaves the humble foreign businessman stuck in a hectic crossfire of toasts, often consuming, or not consuming, at the wrong time – but also an opportunity to say nice things and give face to those around them by proffering one’s own platitudes.

As for holding one’s Baijiu? Practice, practice, practice.

Lesson 2: Speak The Language

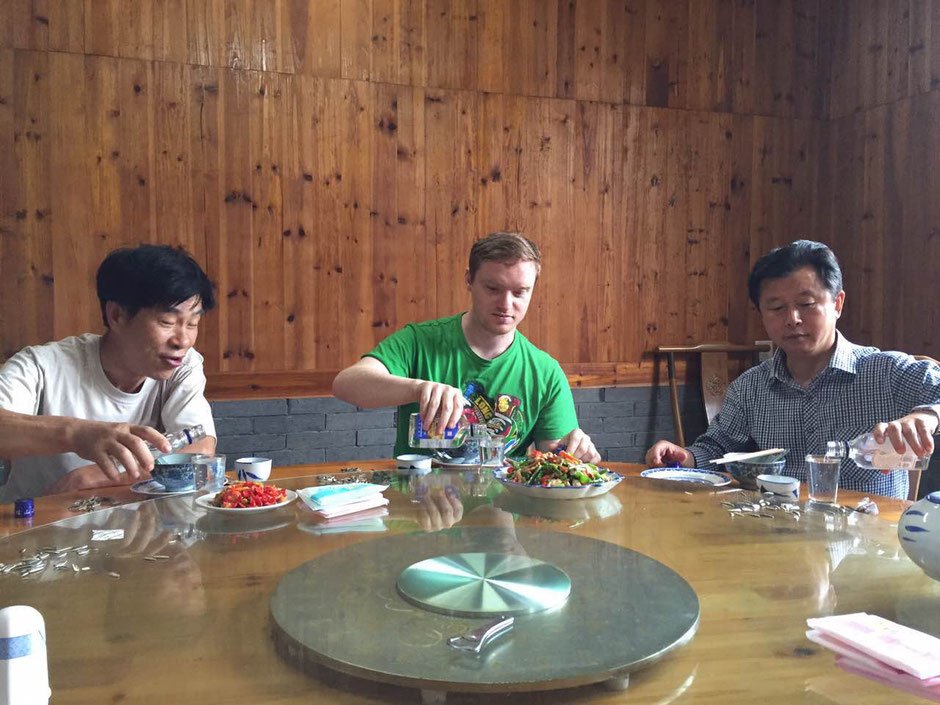

Obviously, this is a huge asset in a place where no one speaks a word of English. Being a foreigner, this will be hugely respected, but remember you will always be a foreigner, even if you can communicate clearly. This can often be infuriating. My delicate line of questions to Mr Jin (picture pouring Baijiu above left) attempted to pick at the impact of tourism on the area, and how it compares to the village he remembered as a child. He raised his eyes thoughtfully…’no, I’ve got nothing to say about that. You’re English though! Where is your hat and umbrella? What English songs can you sing for us now at lunch? English people are real gentlemen!’. Perhaps we may never see eye to eye on the killer issues of the day. In the meantime, all I can do is continue to learn with Teacher Jin from the village: a 75 year old elder who doesn’t have a word of English behind him. So far things are going well.

Selina, being Chinese is obviously far ahead of me here – but even she is locked out when the locals turn to Wuyuanhua, the local dialect. This is almost completely unintelligible from mandarin: think English and Welsh. Normally, when it comes up at the table, there is something fishy going on that they don’t want us to understand.

Lesson 3: Give Face Wherever You Can

Much has been written in China on the concept of mianzi or face: making people look good in front of their group, peers or kin. A man we might call ‘Local Village Leader A’ helped us organise getting a digger across a derelict plot of land in the village to level our garden. This gave an opportunity for the owner to charge us what he wanted to pass his land. He opened the batting with 4,000RMB – an extortionate figure which had the good Leader A swearing under his breath about ‘stupid peasants’. Whilst we haggled over this, our local party secretary came to look at the site and ask if there was anything we needed help with. We told him about the price, which he agreed was extortionate and immediately summoned Leader A to find a solution. We later discovered it was Leader A who had suggested the land owner should charge us money, the more the better. Whilst nakedly duplicitous, championing the local people’s causes and welfare is his remit. Having to retreat and tell the landowner to halve this (still outrageously high…) caused a huge loss of face: he looked incapable, bent at knee to the party secretary and like a man of mouth rather than action.

Of the many admirable traits of traditional Chinese culture (eg reverence for elders), I would not put ‘face’ at the top of my list. The thin skin of some people to take offence if not made to look good reminds me broadly of Donald Trump on twitter (who is very well respected in China I hasten to add). One’s desire to look good, even in the face of abject personal failure clogs negative feedback loops in work, family, community or society settings. Chatting to Chinese friends in the village and cities, they feel emphasis on face is negatively correlated to education and exposure to the outside world, with criticism and frank and open discussions becoming more commonplace. In this way, the importance of face is diminishing as the country continues to develop. For now, it remains key to life in the village.

Lesson 4: You Need A Local Partner

I simply could not do this without the tireless work and expertise of Selina and her family. My mandarin is reasonable, but there’s no way I can hold my own in a loud fast group conversation discussing archaic legal terms or rural land rules. Beyond language though, is an ability to navigate the wildly ineffective and disinterested departments of local government. I never cease to be amazed by the looks of utter outrage by a rural bureaucrat when you suggest anything other than lunch, a cigarette or a drink. In particular anything that could involve standing up, talking to someone in another room, or turning on their computer are quick to draw a look that could kill. There is one force, and one force alone which can overcome such indifference – the fiery temper of a Chinese woman feeling slighted. Men who return from war talk of a real fear that those who stayed behind could never understand – they should compare notes with the poor young chap at the land registry in the Wuyuan county town.

Beyond expertise and language, legal aspects of the house and the business are infinitely easier when done as a Chinese person. Horror stories abound on the subject of local partners screwing over foreign business (read Tim Clissold’s Mr China). Doing this with family then puts me in the best of both worlds.

Lesson 5: Get Things Done In The Morning

Wuyuan gets very hot around midday, and builders, farm workers etc will retreat for lunch and cool shade. It really is very hot, and no one should begrudge them this. Higher up workers in air conditioned offices will speed off to a restaurant to proceed with the serious business of Baijiu drinking. For this reason, proceed onto the roads after lunch (1-2pm) with caution as they can be particularly lively. Returning to the office on wobbly legs, crashing onto faux leather seats for cigarettes and tea it is then time to ‘plan out the rest of the day’. This normally takes about 1-2 hours, and is done in locked offices, with loud snoring sounds rumbling through the corridors. To their credit, everyone is at desk at 8am, and happily calling us before 7am to ask if we can attend a meeting. Things DO get done here… just not in the way I am used to.

Below: Ed and Lili (Selina’ mum), enjoying a traditionally hearty lunch prepared at the local primary school. The children go home to eat, and the teachers turn a classroom into a restaurant for their friends. I hid from Baijiu by drinking a beer.

Lesson 6: Soft Skills Are Everything

In the village, much remains unsaid. People are nervous about saying too much, lest they get themselves, or someone else in trouble, or someone somewhere loses face. Historically in China, popping your head above the parapet meant it would be shot off. This means teasing out the truth behind an issue can be tough. We are still unclear why one family would not sell their land plot to us for our garden – it sits largely unused, and having just spent all their family’s life savings on a smart new house, they cant afford to build anything. Enter: Selina and her family. They are a whirlwind of cups of tea, cigarettes offered, compliments made, face given with whoever they can find. No day is complete without at least 4 trips to various houses to drink tea, chat and discuss an issue in delicately concentric circles, never quite getting to the heart of it. In the case above, I remember calling into teacher Jin’s house for tea and talking about Western and Chinese culture. How family was the heart of everything, but was expressed differently. How impressed we were with how the Chinese venerated their elders. And how Teacher Jin’s sister-in-law in particular cared for her ailing father. And how good this meant her temperament was. (His sister in law was the land owner we were trying to buy from). Sensing where this was going, he stood up, said ‘thanks for coming’ and marched off to pick bamboo in the hills. After about 5 of these tea chats, we got to the subject, and he took us to her house to discuss it with her.

To work well in the village, you must play the long view, always building your network, dropping in for tea and never lunching alone just in the knowledge that you are cultivating a relationship that might be useful someday, even if the benefit is currently unclear. As an outsider in particular, building trust is slow. Selina and her family in particular are excellent at this.

Lesson 7: Blood Is Thicker Than Baijiu

Almost every member of every story I recount involves a man named ‘Jin’ – secretary Jin, teacher Jin, uncle Jin, young Jin. Given the traditional and isolated nature of Wuyuan villages in particular, everyone is related. Our best weapon in times of an impasse is Selina and her mother making elaborate flowery speeches, and Ed drinking Baijiu. This will normally result in everyone coming to an agreement, backslapping, smiles, shaking hands and outpouring of bonhomie. Roughly half the time these agreements still hold up after everyone has napped (see rule 5). The leading reason for going back on an agreement is that people will never, ever go against family. To give us face they will say yes, yes fine, but if Dad, Brother etc disagrees later then ‘that is that’. Buying land in particular brought out 20 members of one extended family, telling us where to measure from, which tree was theirs, shouting protest at any outcome we came to, for fear of not getting the best possible deal. The strength of all Chinese family bonds are very impressive, and are something perhaps we have lost in the post-industrial West. As a foreigner trying to sneak through the cracks in these bonds to buy land or curry favour though, they can prove a hurdle no amount of Baijiu can overcome.

Lesson 8: No Means Yes

As described above, doing nice things, giving face and dropping in on people is essential to achieving your objectives. The actual act of doing such nice things is surprisingly difficult. Every offer is met with ‘I couldn’t possibly’, ‘your money is no good here’ etc. As an Englishman, I am used to hearing ‘you shouldn’t have’, or perhaps politely refusing the first offer of a drink. The villagers however, elevate this to a sort of full contact sport. Watch the video below as Selina attempts to pay JinYuanShui (a previous owner of our house) for a table we bought from him – a rare and fine old piece of the house which we want to preserve. He gains face by being able to tell the other villagers he has turned a tidy profit. Everyone in the village knows everything, and the price he would get from us would have been a conversation around Mah Jong tables for some time. To not pay him would be outrageously rude, result in a catastrophic loss of face and an unacceptable for all involved: you’d struggle to discern this from his reaction though. Also note lesson 7, where yes can just as frequently mean no, for different reasons.

Lesson 9: You Need The Communist Party

A bit like the Force in Star Wars, the party are not always visible, but are an invisible power, binding everything together. After months of knocking on doors of old houses (‘hello, do you live here? Can we buy your house please?’), it took an introduction to the local party secretary to really get the ball rolling. He immediately told us plans for development in each of the villages, which houses where available, who to talk to about a deal etc. Their ways of working are different to what we might be used to. Everything is an exercise in making one’s boss look good, so the best way to curry favour is to help a local big fish make an even bigger fish look good and get the credit. Cigarette ends seem to grow as if on trees to bursting point, like a tropical flower. Much of how they do things I find archaic, and contracts for development projects do seem to cost a bit more than you think they might. I can not fault them though, for heaving the hundreds of millions out of abject poverty. They are not good at running world class, artistic, bohemian cities and promoting soft power globally. Their skill set is in building roads, schools and running water in the lowest level villages throughout China. For all their faults, their merits are most evident in Wuyuan.

Lesson 10: Don’t make a plan

This has been a hard pill for me to swallow, and speaks to the difference between Chinese and Western business practices. In China, nothing is certain – the economic and political sands are constantly shifting beneath your feet. If you see an opportunity, grab it now, make your money and get out before a government agency takes the land, a bigger competitor swoops or the market collapses. Who can say in a year’s time what anyone will be doing?

As a diligent young Englishman, I have written a business plan, though I suspect the Chinese see this purely as an academic exercise. The richly detailed 200 page architect plans? Concept art which builders can look to for inspiration before they decide what to build.

If we try to book people’s time in advance, they will nod and just say ‘lets talk about it on the day’. Similarly, if we need to attend a meeting with the local government, we shall normally be given an hour or two’s notice: a gruff phone call saying ‘be here at 3pm’. As much as I have tried to push through pre-planning, its meaningless if you’re the only one sticking to it. To his credit, our master builder Yuzong is taking scheduling seriously. Lets see how the works pan out before I start singing from the rooftops.

One Year In The Village: My Conclusions So Far…

Every part of China is different – but when you only focus on one village there are clearly defined rules and practices to follow. The ‘relentless energy’ of the Shanghainese? It disappears under a cloud of tea, cigarettes, Baijiu and naps. Never venturing an opinion? Whilst people are loathe to tell you what is really going on, I’ve hit no shortage of people wanting to put the world to rights and tell me all about the English’s penchant for hats and umbrellas.

As my tone suggests, yes this REALLY IS frustrating – but I’m in year one of a learning curve. There are so many wonderful things to enjoy doing business and working here, compared to the big smoke. The slow pace of life, building deep and rich relationships, long lunches and strolls in the sunshine whilst everyone else has a snooze. I wouldn’t change it for the world.